I originally wrote this for The RoadLess Travel Blog on May 14, 2013, when I was sailing around the world with the US Navy as an at-sea NC-PACE Instructor.

Towards a Theory of Solitude

I’ve been developing a theory of solitude.

I have been developing this theory because as I write the story of my life (or as I have it written for me), I don’t know if I like the idea of being on my own more than I actually like being on my own. That is to say, I don’t know if I like solitude in practice or only in theory.

Before I go any further with this theory, I must first make a distinction. When I say solitude, I mean the “state or situation of being alone.” This is vastly different from loneliness, which “refers to a lack of companionship and is often associated with unhappiness.” As such, loneliness is a sad state of being; solitude, on the other hand, may (or may not) be a sad state of being. A person can be in a crowd and feel lonely, but this is obviously not solitude. However, when a person is alone, regardless of feeling, there is no one else around; this is solitude. Again, I simply propose a theory on the “state or situation of being alone.”

As I said before, I have been developing a theory of solitude. I have been developing this theory because solitude is nuanced; it carries the weight of being alone (and here is where the loneliness often creeps in), but it also has the width of meaning beyond just the state of being alone. The eighteenth-century writer and politician Edmund Burke, in Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful, also believed this, since he proposed that solitude leads to the sublime or a state of personal transcendence. Ergo, solitude is romantic; austere; rugged. Solitude is potent.

When thinking through the subject of solitude, I am instantly reminded of two individuals who were subjected to solitude but thrived in spite of it: 1) poet Emily Dickinson was obliged to live within the walls of her mother’s house for 30 years, and yet she produced some of the greatest American poetry the literary canon has ever seen, and 2) the Apostle John was sentenced to exile upon the tiny Greek island of Patmos, and yet he produced the book of Revelation. Both Dickinson and the Apostle John had solitude flung upon them in compulsory ways; in spite of it, though, they thrived. Others, however, chose to shoulder solitude. Two other examples come to mind: 1) author/adventurer John Muir trail-blazed the Sierra Nevada mountains for years at a time, and 2) author/philosopher Henry David Thoreau learned to be self-sufficient as he exiled himself to Walden Pond in Concord, Massachusetts. These two fascinating authors/thinkers led lives, at least for a time, of transient solitude. They were constantly on the road or in the wilderness. And when considering their vagabond lifestyles, one is left to wonder if they were searching or escaping. Only they could fully answer that, but if they were alive today, I would venture to say that their answer would contain shades of both search and escape. Whatever their motive, they were constantly on the move. Quite simply, they were men who refused to settle.

However, when I think about the notion of settling and about the term itself, there is much ambivalence. I wonder if settling was the very thing that Muir and Thoreau were simultaneously searching for and escaping from? Were they searching for that place, maybe even that utopian locale, that they could in fact settle? Or were they escaping because they refused to settle for the trivial, the mundane, and the average? Or maybe still, they refused to settle for the geographic, ideological, or societal borders that hemmed them in– or at least they felt that hemmed them in. Maybe they were searching to settle in the utopian locale because they refused to settle for the ordinary. If any of this is even remotely true, then it helps to explain why they attempted to loosen the grip of that which potentially governs: geography, ideology, society, or even self-advocacy.

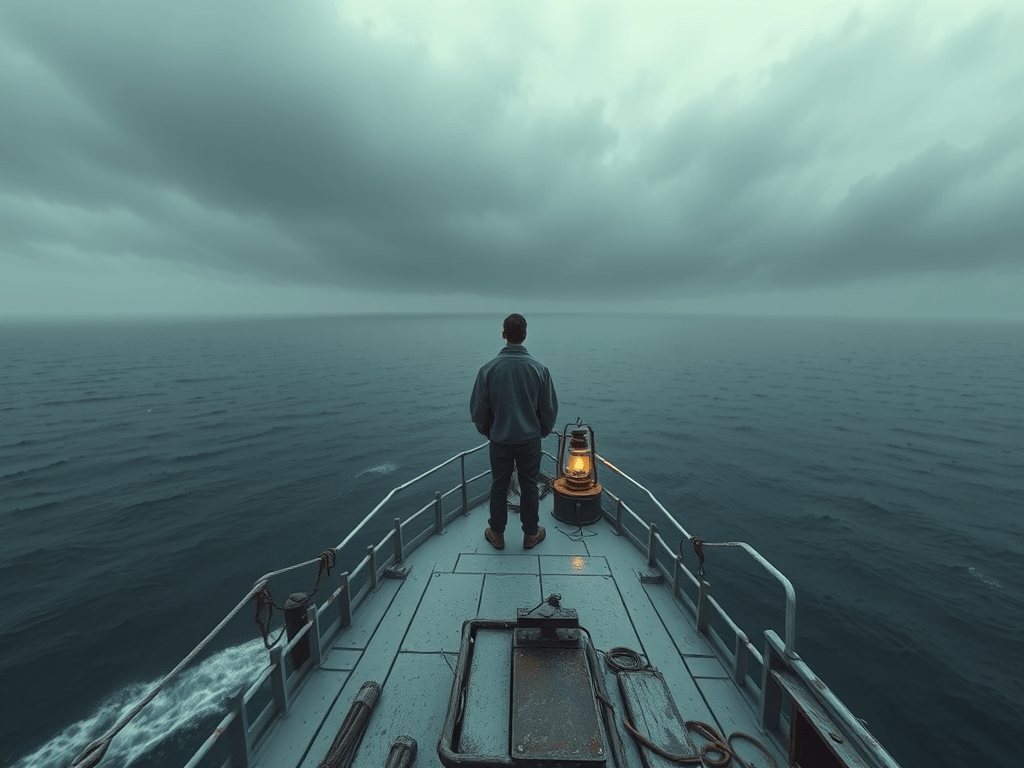

This also helps to explain why they chose to walk headstrong into solitude. Solitude: the road; the horizon; the wilderness; the sea – all metaphors for searching, salvation, and soul. Nary an individual has spent time journeying upon the road or walking into the distance or getting lost in the wild or floating upon the sea and not contemplated his or her own existence, purpose, direction, or lot. Solitude, especially solitude in nature (i.e., upon the road, in the wild, on the sea), inspires awe, an awe that isn’t found anywhere but by being alone in nature. Ralph Waldo Emerson, Thoreau’s mentor and the founder of American Transcendentalism, mentioned this awe-inspiring effect of nature in his own writing:

“Standing on the bare ground,– my head bathed by the blithe air and uplifted into infinite space,– all mean egoism vanishes. I become a transparent eye-ball; I am nothing; I see all; the currents of the Universal Being circulate through me; I am part or particle of God.”

This awe filled state wasn’t experienced only by Transcendentalists (Emerson and Thoreau) alone. It was also felt by one of the most scientific minds the 19th century, Charles Darwin. As he writes in his autobiography,

“In my journal I wrote that whilst standing in midst of the grandeur of Brazilian forest, ‘it is not possible to give an adequate idea of the higher feelings of wonder, admiration, and devotion which fill and elevate the mind.’ I well remember my conviction that there is more in man than the breath of his body.”

Both Emerson and Darwin, as I am sure with Thoreau and Muir as well, found that being alone in the wild was a profound experience. An experience that allowed them come into contact with exterior and interior places that made them reflect. Thus, solitude is a contemplative time, a time when self comes face to face with The Self. Emerson, Darwin, Muir and Thoreau all knew this; and this is why the wild became their form of solitude. If they were going to loosen the grip of governing forces, they were going to have to remove themselves from those forces; they were going to have to be alone.

Being alone, however, especially when engaged in the art of travel, like those examples listed above, is not without its peril: there is no one to help carry the load, no one to help guide the way, no one to help watch your back; there is often no help whatsoever. Consequently, solitude is scary. I said earlier that Edmund Burke in Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful believed that solitude leads to the sublime; an element of the sublime, however, is terror; and for Burke, “terror is a passion which always produces delight when it does not press too close” (42). Thus, solitude is sister to the sublime, and they are both cousins to that which is scary.

In spite of this Edmund Burkeian “terror,” solitude is a place many venture into for the sake of retreat, reflection, and even reward. And for Muir and Thoreau, the rewards in the wilderness were great: for Muir, he fostered an appreciation for nature and so birthed a movement of conservationists; and for Thoreau, he discovered a spirit of self-reliance and self-reflection and helped carry on Transcendentalism.

And it is precisely at this point that helps me illustrate what I said earlier: solitude is potent; solitude has the width of meaning more than just the state of being alone. The rewards that were reaped by Muir and Thoreau were reaped as a result of solitude and all of its various accouterments. It was from the silent scream of a self-imposed solitude that the stories of Muir and Thoreau continue to resound to this day. Without their time spent alone, their stories might not be as potent. But because they did something extraordinary by way of time spent alone, the rest of us want to hear about it; the rest of us want to share in it.

This idea, however, is nothing novel. It seems to be a universal principal, one that Christ and Buddah and Ghandi understood: venturing alone into the wilderness is one way that people find something of worth. As such, those who chose the wanderer’s way, usually have a story to tell, one that most everyone else wants to hear; and they are stories that offer adventure, not just of the exciting kind but of the overcoming kind; and because of that, they are universal stories.

However, before I continue, I feel it is important to take stock of what my mental wanderings have thus far accounted for, especially since I said at the onset that I am developing a theory of solitude. All I have managed to say to this effect is that solitude is potent; it is reflective; it is possibly the manner in which individuals arrive at the sublime; it is scary; and it is what Muir and Thoreau embraced–but that isn’t a unified theory just yet. In order to continue to working towards some sense of unity, I must meander on. I must diverge from the notion of solitude momentarily in order to express how stories of solitude (as seen with Muir and Thoreau) are ultimately the stories that matter because they are the stories of all of us.

The Monomyth/The Hero’s Journey:

As such, allow me to introduce a philosopher to accentuate the idea of the universal story. Joseph Campbell, in his 1949 book, The Hero With a Thousand Faces, about the manner in which narratives or stories, especially the good ones, follow a common universal pattern; he called this pattern the Monomyth. My synopsis of the Monomyth follows:

The main character or protagonist is called out of his/her ordinary life to embark upon a journey. If the protagonist chooses to accept the call, he/she must then face a series of trials or tasks. If the protagonist survives or overcomes these tasks, then he/she may acquire great gift(s) or, as Campbell called it, “a boon.” Once the boon is acquired, the protagonist may decide to return to the world that he/she once lived in to share the gift of the boon. If the protagonist does, in fact, decide to return, he/she must face all the challenges that a return journey poses before they can successfully share the gift(s) they have earned. Finally, once the protagonist does return to their world/life, the boon may now be used to dramatically improve the world.

Campbell gives more stages to the Monomyth that I do here. Actually, he gives 17 separate and distinct stages. Here are the names of each stage of the Monomyth:

- The Call

- Refusal of the Call

- Supernatural Aid

- The Crossing of the First Threshold

- Belly of the Whale

- The Road of Trials

- The Meeting with the Goddess

- Woman as Temptress

- Atonement with the Father

- Apotheosis (or Climax)

- The Ultimate Boon

- Refusal of the Return

- The Magic Flight

- Rescue From Without

- The Crossing of the Return Threshold

- Master of Two Worlds

- Freedom to Live

Campbell says that not all great stories display all 17 stages of the Monomyth, but all great stories do have at least some of these stages. And it is precisely because of this fact, I find a few things to be interesting, if not surprising, about the Monomyth.

First, the individual that goes through these 17 stages, at least in part, is referred to not simply as the protagonist of a story but The Hero. In fact, the Monomyth is otherwise know as The Hero’s Journey (and from here on, I will use the two terms “Monomyth” and “The Hero’s Journey” interchangeably since they refer to the same thing). Therefore, the stories of John Muir during the course of his lone travels and Henry David Thoreau as he lived on Walden Pond, in spite of the fact that they are non-fiction stories, are that of The Hero. Muir and Thoreau are the heroes of their respective stories, not simply the protagonists, because of the manner in which they, too, were called out of their ordinary worlds, faced trials and solitude, earned a boon, and returned to the world with the boon. The stories of Muir and Thoreau are examples not only of shouldered solitude but The Hero’s Journey.

The second thing that I find interesting about the The Hero’s Journey is that since Campbell believed the Monomyth is universal, it applies to all great Hero-stories, whether fiction or non-fiction: Dickinson, The Apostle John, Muir, Thoreau, Prometheus, Odysseus, Buddha, Moses, Christ, Frodo, Lincoln, and even Skywalker (George Lucas actually credits Campbell for helping to inspire Star Wars). Thus, The Hero’s Journey may in fact shape all great heroes and therefore all great stories, fiction and nonfiction alike.

The third thing that I find so interesting and surprising about the Monomyth is this: if The Hero’s Journey does in fact shape all great stories, then we, too, are shaped by The Hero’s Journey, for so much of our collective consciousness and culture stems from the world’s great stories. And since we all know that society’s culture and consciousness is made up of individual stories and and individual lives, then the Monomyth is, at least in some small measure, a part of each one of our lives.

Thus, and in an effort to better chart the line of thinking I am attempting to establish: the Monomyth/The Hero’s Journey is the universal pattern of all heroes/stories; and all great stories, both fiction and nonfiction, are influenced, at least in part, by the The Monomyth; and all great stories are simply the collection of society’s culture/consciousness; and individual stories/lives are what make up society’s culture; then the Monomyth influences individual stories/ lives.

The Hero’s Journey = The Everyday Hero’s Journey

For me, this idea that the The Hero’s Journey influences individual stories and lives helps to explain why, when Campbell spells out his 17 stages, some of those stages look all-too-familiar; they aren’t just the stages of the classic hero– what most of us come to think of when we think of “hero:” Superman, Batman, 9/11 rescue workers, Medal of Honor recipients, Jedi Knights; these stages are those, at least in part, of our own individual and sometimes ordinary lives.

In fact, some of Campbell’s stages are stages that I been in at one time or another. For instance, I have been in the proverbial Stage #5: “The Belly of The Whale;” more truthfully, however, I have been in the belly of many-a-whales. Naturally, this phrase refers to the story of Jonah found in the Bible. If the reader is unfamiliar with the story, here is a brief synopsis:

Jonah was commissioned by God to go and preach to the city of Nineveh. However, when Jonah ignored and therefore disobeyed God’s command by attempting to flee by way of sea, Jonah was tossed overboard and ends up being swallowed by a whale. Hence the term, “in the belly of the whale.” In spite of the dire situation that Jonah found himself in, the whale ended up being his method of salvation. Had he not been swallowed by the whale, he would have surely died in the sea. And it was probably this realization that led Jonah to make the decision to go and fulfill the job that God had originally commissioned him for and preach to the city of Nineveh.

Therefore, when I say, “I have been in the belly of many-a-whales,” it is like saying, I have often shirked my responsibilities and found myself in a dire situation that was momentarily horrific but ultimately good– and it was “ultimately good” because the situation ultimately got me to do the thing that I should have done in the first place.

What’s more, as I continue to read Campbell’s list, I read stages like #14: “Rescue from Without” and think about all of the times that I needed rescue from without, or that is to say, I needed help from a source outside of myself. And usually that help came from family members and/or friends. Or I read #8: “Woman as Temptress” and think about the times when there was literally some woman or who stole my attention, time, and even heart. Now, this isn’t to say “Woman” is the only “Temptress” that I or Campbell refer to; the Monomyth is not patriarchal. The Temptress can, and has been for me, The Tempter as well: be it money, ego, or any other object which stole my attention, and time, and heart. Therefore, Stage #8: “Woman as Temptress” is yet another stage, like “The Belly of the Whale” and “Rescue from Without,” that my own life has had to negotiate.

So, as you can see, The Monomyth/ The Hero’s Journey is quite possibly the descriptive pattern of not just the superhero (or super story) but the everyday hero (or everyday story). Clearly, we all have unique lives and experiences, but sometimes what makes humanity great is not so much our amount of collective differences, but our amount of collective similarities. As such, how many people have found themselves upon Stage#6: “The Road of Trials”? Or how many people, like I at times, are in need of Stage#3:“Supernatural Aid”? And just about every human on this planet seems to be searching for Stage #17: “The Freedom to Live.” To reiterate, the Hero’s Journey then is not just the pattern that John Muir and Henry David Thoreau’ s respective stories follow; it is the same pattern that our everyday and often ordinary stories follow.

Solitude is the Great Impetus to a Truly Heroic Story

A questions still beckons though: why, if The Hero’s Journey is quite possibly the universal pattern that both the ordinary and extraordinary hero share, do Muir and Thoreau have the attention and adoration of society in a way that the everyday hero does not? Why is their (the extraordinary) story written for all to read and my (the ordinary) story is not? Well, I believe the answer to that is simple: 1) Muir and Thoreau were probably more interesting and intelligent than I (or most) to begin with, and 2) Muir and Thoreau chose to dauntlessly live through more stages of the Monomyth. That is, they didn’t just cross “The Road of Trials;” they lived there. As such, when they needed “Supernatural Aid” because they were squarely on the “Road of Trials,” they didn’t get to go home like the rest of us; they kept on moving down another Road. They were the consummate traveler, and make no mistake, there is a big difference between a tourist and a traveler: a tourists visits; a traveler lives within (or sometimes without). Most the time spent by everyday individuals upon The Road of Trials is spent in passing, as a commuter. For Muir and Thoreau, however, the Road of Trials was not simply a commuter’s path to and from the familiar (as in commuting to and from home and work or to and from home and school). Their Road of Trials was the commune with the Self and possibly “the Father” or even “The Goddess.” What’s more, as I have been constantly stating, Muir and Thoreau spent their time on that Road alone. If they hadn’t, their stories might not be as potent. But because they did something extraordinary by way of time spent alone, the rest of us want to hear about it; the rest of us want to share in it. And their Road of Solitude made their stories worth sharing.

Living upon The Road, as I mentioned earlier, is a contemplative time, a time when self comes face to face with The Self. And from these chance meetings with The Self, an individual is often brought to some sort-of epiphany, or deeper awareness, or inner-struggle, or, as Burke pointed out, sublimity. Author/theologian G.K. Chesterton wrote that these meetings with The Self were profound because, as Chesterton said, “Self is the Gorgon.” Now, if the reader is unfamiliar with what a Gorgon is, the mythological creature Medusa with her hair of snakes and ability to turn her spectators to stone was a Gorgon. As such, and in Chesterton’s view, a meeting with The Self is a meeting with The Gordon. Interestingly enough, the dictionary uses one definition to define the Gorgon as, “a fierce, frightening, or repulsive woman.” Therefore, Campbell’s Stage #8:“Woman as Temptress” might very well be explained as a meeting with The Temptress that is The Gorgon Self (and I think Freud and his thoughts on the Ego and Superego would agree: the meeting with the Self or one’s Ego is a meeting with The Gorgon).

Thus, when one is upon The Road, The Self (or Gorgon or Ego) may very well be the thing that we are either searching for or escaping from; it’s quite literally The Road to Discovery of one’s Self. However, one doesn’t make their way onto The Road of Discovery until they engage in the art of travel. This is why Stage #1: The Call and Stage #4: The Crossing of the First Threshold (a.k.a. The Acceptance of The Call) are so important; they take us out of what is domestic to into that which is foreign. And it has been amply discussed and detailed by many social psychologists and philosophers (Jonathan Haidt, Antonio Gramsci, Michel Foucault, etc.) that a foreign journey teaches the traveler not just about the place they have traveled to but equally about the place they have traveled from. This is probably the most keen aspect of travel: the ability to teach us about ourselves. Gregory Clark in his 1998 article, “Writing as Travel, or Rhetoric on the Road,” mentions this when he said, “…think of the traveler as one for whom the road presents… a succession of opportunities to “revise” the self (399). Thus, The Crossing of the First Threshold or “The Acceptance of The Call” takes us into a new place where we can discover The Self– and maybe an altogether “revised” Self; after all, no one wants to stay as the hideous-looking Gorgon.

“The Call” and “The Crossing of the First Threshold,” then, is one of the best methods a person can come face to face with The Self. Solitude is simply of byproduct of one’s choice to accept “The Call.” Again, for Muir and Thoreau, the acceptance of going up and out of their ordinary worlds took them onto the road and into the wild, but that solitude allowed them to dive deeper into the narrative pattern. That is to say, once they were on their own, they could have their “Meeting With The Goddess” (Stage #7), experience “Woman as Temptress” (Stage #8), and find “Atonement With The Father (Stage #9). And it seems readily clear to to me that if an individual/hero is to encounter these particular stages more profoundly within his or her own story, they require solitude. For no one ever truly met with The Goddess or The Father in a crowd; meetings such as these are deeply personal and require solitude. Again, this is why the “road present[s].. a succession of opportunities to “revise” the self” ; no one encounters The Goddess or The Father without profound personal change.

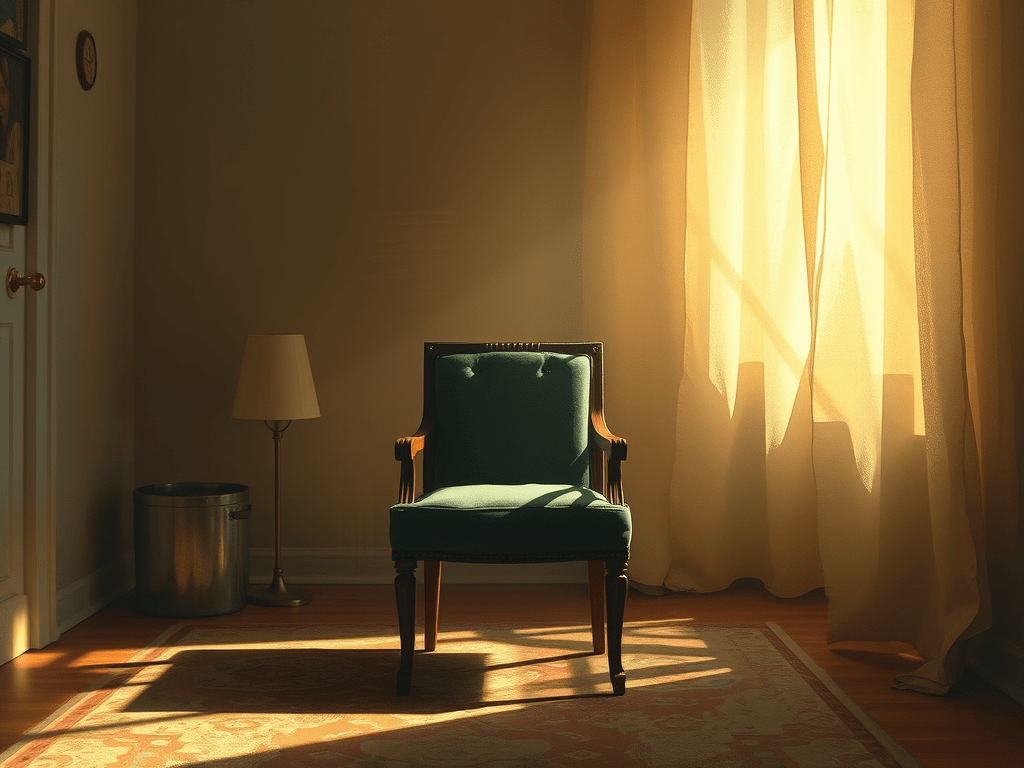

And this is precisely why there is something austere, and rugged, and all together potent about solitude and the idea having one’s world strapped to one’s back. It is freeing. We live in a world that is inundated with stuff. Even the late, great comedian, George Carlin, once joked, (and I am inclined to want to preemptively apologize to the reader for the following profanity, but I know George Carlin would have done such a thing; therefore, I won’t either): “A house is just a place to keep your shit while you run out and get more shit.” Quite simply, we live in a world where “shit,” and not just physical “shit” but mental, emotional, and societal “shit” as well, hinders. A May 7, 2013 New York Times article entitled, “Brain, Interrupted” by Bob Sullivan and Hugh Thompson discusses how much the “shit” of the world, all of our daily interruptions, truly hinder: “the distraction of interruption, combined with the brain drain of preparing for that interruption, made…[individuals] 20 percent dumber.” Thus, the “rapid toggling between tasks” that the article discusses and that everyday life requires drains the potency of our brain power. This is why solitude is freeing. It eliminates the “shit” which literally robs us of our ability to focus.

This is also why solitude is the great impetus to a truly heroic story: all of the stuff, shit, chatter, expectation, baggage, responsibility, entertainment, hustle, toggling between tasks and what I will label from here on out as noise gets in the way of hearing anything that resembles The Call. More importantly, however, all of this noise keeps us from having our Meeting With The Goddess or gaining our Atonement With The Father or finding The Ultimate Boon. One simply cannot come face to face with The Self or The Goddess when there are too many faces (or noises) in society vying for our attention. This is why Scripture teaches in Ecclesiastes 7:4 that, “The heart of the wise is in the house of mourning, but the heart of fools is in the house of pleasure” (New International Version). Another version of the Bible, the NET Bible version, but of the same scripture helps illustrate the point better: “Sorrow is better than laughter, because sober reflection is good for the heart.” I repeat, “sober reflection is good for the heart.” Solitude rids us of the noise and affords us the opportunity to combat The Self and commune with The Father or The Goddess. This probably explains why Jesus went alone up to the mountainside to pray (Matthew 14:23; Luke 5:16); the reflection he found in solitude was good. Jesus knew this. Muir and Thoreau knew this. All the great heroes of literary lore knew this.

The Road that leads to solitude is a good one.

Truly Great Stories Require a Hero With a Boon & A Heart to Share

The Road that leads to solitude is a good one because it allows the Hero to wrestle with the Gorgon (the Self); it allows the Hero do discover and possibly defeat the Temptress; it allows the Hero to meet the Goddess; it allows the Hero to bow before the Father; and it allows the Hero to reach Stage #10: Apotheosis (or Climax)– all things which are profound and life altering. But these stages of a truly great story, as depicted by Campbell, aren’t worth much if the Hero never receives his or her Gift/Boon and/or never returns to their world in order to share that Gift/Boon.

Thus, if a Hero (everyday Hero or super Hero) never experiences Stage #11: “The Ultimate Boon” or, after receiving the Boon, decides that they don’t want to participate in Stage #15: “The Crossing of the Return Threshold” (a.k.a. The Return Home), then what was the point of “The Call,” “The Road,” or the time spent in solitude? The answer is none. There is no point to solitude that does not have the goal of improving one’s Self and one’s Society. Solitude solely for the sake of solitude is simply loneliness.

The Road that leads to solitude is good if and only if that solitude leads to a self-awareness and that self-awareness leads to social improvement. This is why Muir and Thoreau’s respective stories were so powerful. This is why their stories were worthy of living and, therefore, worthy of telling. They lived in solitude, but that solitude had a goal: a Boon that could be shared. Solitude that lacks the all important Boon (or gift) is a solitude that is ultimately lacking. If a Hero ventures into the wind or the wild with no other purpose than being a troglodyte or a hermit, their solitude is ultimately selfish. Viktor E. Frankl was an Austrian psychiatrist/writer that was imprisoned in Hitler’s concentration camps. He survived his horrific imprisonment and afterward wrote about the way in which a person can reach a state of true happiness by way of a life filled with philanthropy. In his book, Man’s Search for Meaning, he called this state, self-transcendence. A person, in Frankl’s view, “the primordial-anthropological fact [is] that being human is being always directed and pointing to something or someone other than oneself: to a meaning to fulfill or another human being to encounter, a cause to serve or a person to love.” Thus, a person becomes fully human not only by finding and facing one’s Self, as one of the consequences of solitude achieves, but “by forgetting himself and giving himself, overlooking himself and focusing outward” (italics mine). Or, in other words, by sharing the Boon.

John Muir and Henry David Thoreau were the Heroes of their respective stories because 1) they listened to “The Call” and chose a path of solitude, 2) they found discovered themselves and achieved their Boon, and 3) they retuned home and shared that which they learned and achieved.

Consequently, a truly great story requires a Hero with a Gift and a heart to share that Gift. And more often than not, that Gift or Boon is the gift of a revised Self– one that is all together more virtuous, stronger, grounded, and brave. The Hero is now, because of his knowledge of the local and the foreign, the namesake of Campbell’s 16th Stage: “The Master of Two Worlds.” The Hero is the Master of both the old Self (or world) and the new. He can thus share this Gift, this knowledge of an improved Self, with his/her society. Jesus may have gone up to the mountain to pray to God, but he always came back down the mountain to share with the people that which he learned by his time spent alone. And it is here, with the sharing of one’s Gift, with the giving away of what one gained while living in solitude upon the Road, that the Hero seems to find that one thing that every Hero is ultimately looking for: the ever elusive Stage #17 of Campbell’s Monomyth: “The Freedom to Live.”

My mother always told me, “there is a big difference between living and merely existing.” Those that are only concerned with the preservation of themselves and their well being seem to be of a class of individual that only exists in this world, for their goals are only with the Gorgon. However, those that that are found to be of the class of individuals that truly live seem to be those that face and defeat the Gorgon. In Greek mythology, Perseus was the son of Zeus and, among other great personal feats, defeated the Gorgon Medusa. Once defeated, Perseus gave the head of Medusa to Athena, the patron goddess of Athens. What makes this act so interesting is that Athena was also the goddess of Wisdom, and in literature she is often allegorized as the very personification of wisdom. Thus, Perseus defeated the Gorgon and gave it over to the wisdom of the Goddess. The key to truly living or “The Freedom to Live” may be housed in one’s ability to defeat the Gorgon, giving it over to The Goddess, and returning home (as Perseus did) to share his Gift with people.

A Theory of Solitude: Awe Inspiring

I started this essay because I wanted to develop a theory of solitude. I had been developing this theory because solitude, as I said previously, is nuanced. It carries the weight of being alone and the width of meaning more than just being alone; it is sublime; it is romantic; it is austere; it is rugged; it is potent. However, I had come to these initial conclusions about solitude because I, like Muir and Thoreau, have over the course of the last three years been living in a state of solitude while out to sea or traveling in foreign territories. I have been on my own exploring mountains and forests and deserts and cities and seaside ports all by myself. These travels have been good; however, they have not been good simply for their own sake (that is to say travel just for the sake of travel). They have been good because of the way that have provided me with the opportunity to come face to face with my Gorgon in a way that I never could have while being surrounded by all of the familiar noise of home. For when I, or any of us for that matter, are so comfortable with out location, we become complacent and quite possibly stagnant; we have been turned to stone by Medusa because we stared to long at her. Instead of defeating the Gorgon, we let her calcify our individual development. Thus, when we get out of our familiar situations, answer The Call, get upon The Road, we are no longer primarily concerned with trying to change our environment so to suit our own changing needs, but we are concerned with changing our selves so as to adapt to the changing situation– -and that’s when we end up finding The Ultimate Boon. This is an idea that Viktor Frankl, again in his book Man’s Search for Meaning, gets at when he says, “When we are no longer able to change a situation, we are challenged to change ourselves.”

Solitude brings us face to face with our Selves so that we can actually overcome our Selves. As when Perseus met Medusa, facing the Gorgon for the sake of staring in awe is grave (as Peruses initially wanted to do); but facing the Gorgon for the the sake of conquering is good. Once the Gorgon was defeated, then it was safe for Perseus to stand in awe not of the Gorgon but of his surroundings, the gods, and the Boon which he had acquired. Only this type of awe, the one that looks outward and on to other beings, is good. Jonathan Haidt in his 2013 book, The Righteous Mind: Why Good People are Divided on Politics and Religion, talks about the power of outward focused awe: “The emotion of awe is most often triggered when we face situations with two features: vastness (something overwhelms us and makes us feel small) and a need for accommodation (that is, our experience is not easily assimilated into our existing mental structures; we must “accommodate” the experience by changing those structures)” (264). This is why solitude and travel are so easily the trigger for awe: we are faced with situations that are either vast or need to be accommodated. This is also why solitude and travel help to make for a truly Heroic story: we get to watch the Hero face that vastness and either accommodate the experience (overcome it) or be accommodated (overcome) by it.

Haidt goes on, “Awe acts like a reset button: it makes people forget themselves and their petty concerns. Awe opens people to new possibilities, values, and directions in life” (264). In sum, the awe we find in solitude and nature and travel and in meetings with The Goddess or The Father quiets the noise of everyday life and it helps us open up to “new possibilities, values, and directions in life.” This is also why people, as Haidt says, “describe nature in spiritual terms…[because nature can]…shut down the self, making you feel that your are simply a part of a whole” (254). Again, defeating or shutting down the Gorgon, allows for the Boon to be earned, but more importantly, for that Boon to be shared.

Solitude, thus, is not for one’s own sake alone. Nor is travel, or temptations, or chance meetings with the deity(s). My theory of solitude then is this: solitude signals to the social. Solitude is solitude for a undetermined about of time, but if that solitude to to carry any real weight or worth or potential, it then is always pointing ahead to the social. The time spent alone will not be (or at least should not be) an infinite time; solitude is (and should be) temporary. Time spent in the realm of the social is where meaning is imbued; society is eternal. I suppose this is the essence of Creationism and Christianity: when Christians die, the belief is that they will spend eternity in either Heaven (where God is) or in Hell (where God is not). Thus, the promise of Christianity is either eternal solitude (which would very quickly become loneliness and depression) or eternal society (or communing) with God. This is also the promise of both many belief systems: moving into an either an eternal state of solitude (darkness, emptiness, nothingness) or an eternal state of society (Valhalla, Paradise, Shinto commune with the ancestors).

Whether the stories are the ones recorded in history books (as with Muir or Thoreau) or the one recorded in our own photo albums, the story of the Hero is the story of the individual who faces the his/her Gorgon, stands in awe of something other than one’s Self, discovers the God/gods, achieves their Boon, and then shared their gifts with the rest of the world. Solitude sets all of this in motion, but solitude is not the end of it all, the return is. Campbell called this “The Freedom to Live;” I call it one of the reason for living.

I have developed a theory of solitude: solitude signals to the social.

I have been developing this theory because as I write the story of my life, and I do write the story of my own life, I like being on my own but only for so long. I need to get back to those I love.

I have many gifts that I want to share.

Leave a comment