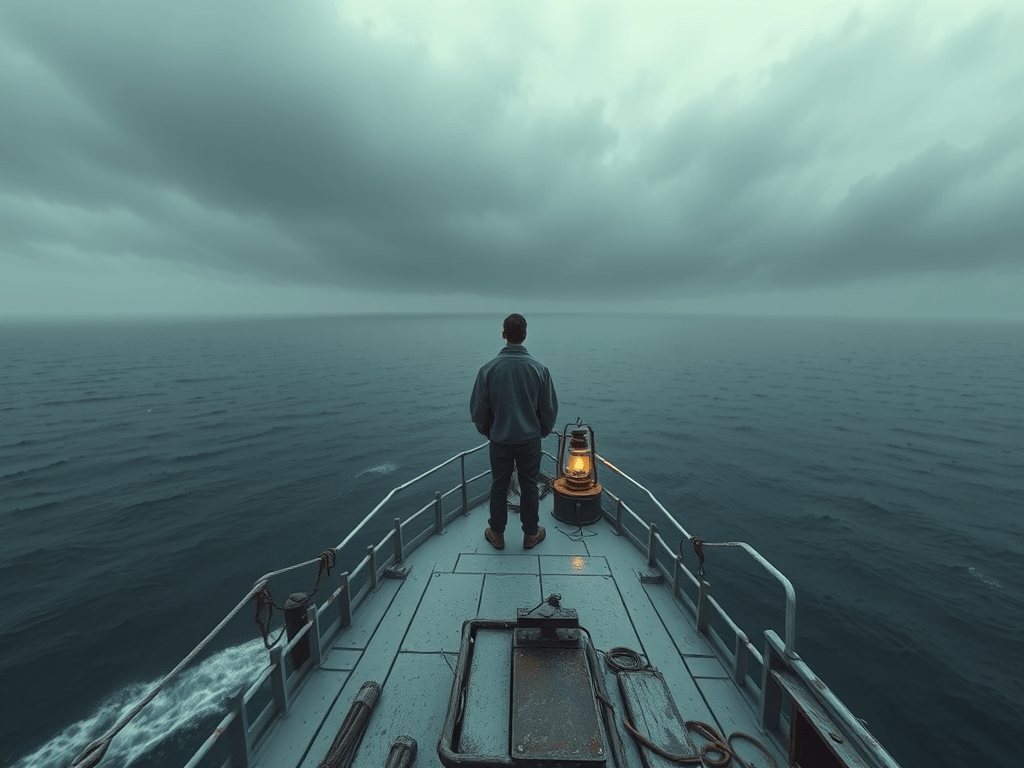

I originally wrote this on August 17, 2012, while sailing in the Arabian Sea with the USS Hue City as an at-sea NC-PACE Instructor.

If you know me personally, then you know I have endured a lot of pain. If you do not know me personally, I will spare you all of the details, but it is the standard list of hurt and heartache: death, failure, divorce, regret. I suppose my story is no more miserable than the next individual who has been given the bitter-sweet gift of life on this earth. My own traipse through tragedy, however, has birthed in me what the Chicana writer, Gloria Anzaldua, would call “La Facultad;” that is, “The Faculty” or an ability to easily perceive and appreciate those who have also suffered. My “Faculty” is why I love Johnny Cash’s rendition of the song, “Hurt.” The somber gravel in Cash’s voice is what makes the lyrics “…I will let you down/ I will make you hurt…” an anthem for the heart’s ability to throb.

My Faculty (again, my familiarity with life’s struggles and strife) is also why, when I read novels like the one I recently picked up in Greece, “Zorba the Greek” by Nikos Kazantzakis, I highlight passages like “…the gods eventually become no more than poetic motifs or ornaments for decorating human solitude..” (145) because they speak me; they register as pieces of human understanding and appreciation for pain and the paths we walk because of it. It’s as if I have some wounds that don’t fully heal and I like to know others carry the same wounds as well. And I know that I am not the only one that finds reassurance in the wounds of the world; Heather King in her memoir, Parched, comments on the same thing. As she says, “I loved the way books looked, loved the way books smelled…my favorites were The Diary of Anne Frank, The Yearling, Uncle Tom’s Cabin: tales of grotesque cruelty and unbearable loss. That was precisely why I liked them. Even back then I understood the real purpose of literature. I didn’t want to hear that people lived happily ever after. I wanted to know that other people suffered, too.” I, like King, appreciate literature, lyrics, and any reflections on the ability of another human being to suffer and endure through that suffering.

This is not to be a pensive piece, however. This is not me wallowing in the waste of wasted opportunities or time. On the contrary, this is me actually looking at the scars I carry, at the scars we all carry, and appreciating them. They make us who we are and who we will someday become. The residue of the past is always permeating the present, and the thoughts, memories, and moments that seem to permeate our minds most poignantly are the ones that hurt– and hurt deeply. But that is okay, because those unpleasant memories carry lessons learned, the promise of future possibilities, and the proof of life endured.

But why am I meandering on about past hurts and their ability to linger? Because I recently read a fascinating article in the March 2012 edition of Wired magazine; it was called “The Forgetting Pill” by Jonah Lehrer. Lehrer’s article discusses the astonishing possibilities and potential problems with a new test-drug; it works, as it’s unofficial moniker: “The Forgetting Pill” suggests, by allowing the user of the drug, as directed by a scientist/researcher, to forget certain memories. It’s not a complete erasure of memory, however. What makes this little pill so astonishing is that certain targeted memories could be permanently erased from the mind. Now, this idea of erasing memories immediately recalls to my mind the movie, “Men in Black,” and the little tampon-looking doo-dad (that’s my unofficial moniker for it) with the flashing light at the end of it that Will Smith uses to erase the memories of the civilians who have seen an alien. Save for science fiction movies or real-life calamity such as amnesia, coma, or a really debauched night of drinking, erasing memories seems to be the result of either fantasy or tragedy. However, an actual pill that can target certain unwanted memories, like a tragic accident, the loss of a loved one, war-time haunts, or a personal assault, may be something else all together.

I will spare the reader all the details of how The Forgetting Pill actually works; and to be completely honest, after reading the article twice, I am not entirely sure I know how it works myself. What I do know, and in the simplest terms, is that the pill inhibits the ability of a protein PKMzeta. PKMzeta is a protein that is housed in the brain that helps us recall memories. As such, scientists have test subjects recall certain painful or unwanted memories, and as they recall them, the drug is administered and, zap!, PKMzeta can’t do it’s job of recalling the memory. In fact, it seems that when the attempt to recall the targeted memory is made, something happens to that particular place in the brain where the memory was– something else is in fact written. It’s akin to storing new information over old information on a re-writable CD.

Now, I will admit that the drug’s ability isn’t quite as cut and dry as I explain; I am simplifying the process of the drug for the sake of talking about it. At this point, the unwanted memories of those who take the pill aren’t completely wiped out; there is still the residue, if you will, of the memory, especially if it is extremely tragic (like 9/11 or a rape). However, the goal of the drug-makers/ researchers is to do exactly as I have suggested: wipe out targeted and unwanted memories completely.

This is not only an astonishing idea– erasing targeted memories by way of a pill– but it shed some light on the way the brain actually works to recall memories. As Lehrer says, “So many of our assumptions about the human mind– what it is, why it breaks, and how it can be healed– are rooted in a mistaken belief about how experience is stored in the brain. (According to a recent survey, 63 percent of Americans believe that human memory ‘works like a video camera, accurately recording the event we see and hear so that we can review and inspect them later.’)” (91). Elsewhere in the article, Lehrer says that when we recall memories, they are less like the replaying of a movie and more like the encore of a play (and thus each performance is slightly different than the last). Therefore, “memories are not formed and then pristinely maintained, as neuroscientists thought; they are formed and then rebuilt every time they’re accessed” (90). For me, and apparently for neuroscientists, this was novel because it helped explained how and why “time heals all wounds.” Part of it has to do with the fact that flesh will organically grow anew; however, the other part of it has to do with the fact that the mind is refashioning our memories, especially our painful ones because they are the ones that we typically recall the most, so that we can “deal” with them. At this point, a pill to erase memory seems to be a mute point.

Regardless, every time we recall a memory, good or bad, more and more pieces of it are recalled incorrectly. Lehrer continues, “We want the past to persist, because the past gives us permanence. It tells us who we are and where we belong. But what if your most cherished recollections are also the most ephemeral thing in your head? Consider the study of flashbulb memories, extremely vivid, detailed recollections. Shortly after the September 11 attacks, a team of psychologists led by William Hirst and Elizabeth Phelps surveyed several hundred subjects about their memories of that awful day. The scientists then repeated the surveys, tracking how the stories steadily decayed. At one year out, 37 percent of the details had changed. By 2004 that number was approaching 50 percent. Some changes were innocuous– the stories got tighter and the narratives more coherent– but other adjustments involved a wholesale retrofit. Some people even altered where they were when the towers fell” (90). As such, something as tragic as 9/11, even after only three years, was for some a memory that became unclear and ultimately contained corrupted content. “Over and over,” as Lehrer states, “the act of repeating the narrative seemed to corrupt its content” (90).

Again, another novel idea: “the act of repeating the narrative seemed to corrupt its content.” There are so many places that this simple statement takes my mind: What about the narratives (stories, tales, parables, memories) that we maintain for family record? What about the narratives we tell ourselves to make peace with the mistakes we have made? What about the narratives we rely on for faith? Do they all contain corrupted content? I do not question because I doubt; I do question, however, because I am a storyteller, because I am story lover, and because I appreciate the value of the story–especially the one that depicts pain and a person’s ability to endure. Does our inaccurate memory make the memory better or does it make it worse? Whatever the answer is to that question, Lehrer offers more insight, “What’s most troubling, of course, is that these people [the subjects of the post-9/11 study] have no idea their memories have changed this much…the strength of the emotion makes them convinced it’s all true, even when it’s clearly not” (91). As such, even if a memory is corrupted by constant recall, it seems that the emotion that is also imprinted on that memory is still very real.

Enter The Forgetting Pill once again. It isn’t just the memory that scientists/ researchers were trying to erase– natural and improper recall can do that. It’s the emotion that is attached to an unwanted memory that researchers want to erase. And, ultimately, that’s what the individual who has suffered the loss of a loved one, who has been the victim of a crime, or has witnessed a horrific accident wants to erase– the negative emotion that is attached to that memory. But what happens to us as a people when we can pick and choose which memories and emotions we want to live with? Sure, I am in favor of being happy, but what happens when happiness is the new drug? What happens when pain is a thing of the past? What does a society look like that has no memory of what it is like to suffer? I don’t know for sure, but I’d venture to say some of the casualties of that society would be empathy, appreciation, discipline, wisdom, and strength. After all, that which is strong (in mind, in body, or in spirit) is that way because it has been tested, tried, and it has endured.

Ultimately, I hope The Forgetting Pill never makes it to the shelves of RiteAid, SaveOn, or Walgreens. I said earlier, “save for science fiction movies or real-life calamity such as amnesia, coma, or a really debauched night of drinking, erasing memories seems to be the result of either fantasy or tragedy.” And I believe, in our pill-popping, needs-are-confused-with-wants society, this little pill is still the stuff of fantasy and tragedy. Fantasy because people who will use it will ultimately be living just that: a fantasy. To erase all of the the terrible things that have happened to us is to ask everyone around us to also live in a fantasy world. The user of the pill may not remember 9/11, but shall the rest of us pretend that it didn’t happen? Besides, what happened to that spirit of “We Shall Never Forget”?

What’s more, the use of The Forgetting Pill is not only the stuff of fantasy, it is the stuff of tragedy. For humans to try and erase the things that hurt us is to loose all the lessons that hurt teaches us. This is a sentiment that Leher also shares at the end of this article: “The problem with eliminating pain, of course, is that pain is often educational. We learn from our regrets and mistakes; wisdom is not free. If our past becomes a playlist — a collection of tracks we can edit with ease– then how will we resist temptation to erase unpleasant ones” (120)? To loose the ability to remember pain is to loose the ability to endure it, and to loose the ability to endure pain is to loose the ability to endure as a human being.

We were made with an imperfect memory. Practical knowledge has dictated this, but current neuroscience proves it. Thankfully, that imperfect memory is why the axiom, “time heals all wounds” is true. Interestingly, wounds leave scars and those scars carry the weight of not just memory but emotion. And I say that one shouldn’t try and forget that emotion by way of whiskey, interpersonal wars, or a convenient little pill. One should, I like I was forced to do, like we are all forced to do, embrace the pain, the memory of pain, and the emotion of the pain. This is how we endure. We all have to traipse through tragedy, but instead of trying to forget for pain, we should turn on some Jonny Cash, sit back, and learn to appreciate the lessons learned, the promise of future possibilities, and the proof of life endured.

P.S.

I wrote this on August 17, 2012 while sailing in the Arabian Sea with the USS Hue City. Since writing this, I had learned that my grandmother, Ruby Shinn, who is 98 years old, was nearing her last days on this earth– as indicated by the fact that the nursing home staff had moved her into the “Angel Room;” the place where they relocate individuals who only have a few days to live. Thus, the fear has been over the last week or so that my sweet grandmother is about ready to pass. I even wrote a brief eulogy that my family would be able to read at the funeral since I would not be able to be there. My aunt, Jane, thought it might be a good idea to read my writing to my grandmother since I would, in fact, not be able to be there; therefore, she did exactly that. Apparently, after my grandmother heard the eulogy, for whatever reasons, she began, as my uncle Ralph said, “rallying.” And the very latest about my grandmother’s health is best shared through my uncle’s own words in an email he sent me:

“Ruby told the nurses the other day that she wasn’t going to die and that she wanted to go back to her regular room. So she has been returned to her old room and is back on the regular schedule.”

I share this here because my grandmother, Ruby Shinn, at 98 years old, is my greatest proof and inspiration for life endured.

Leave a comment