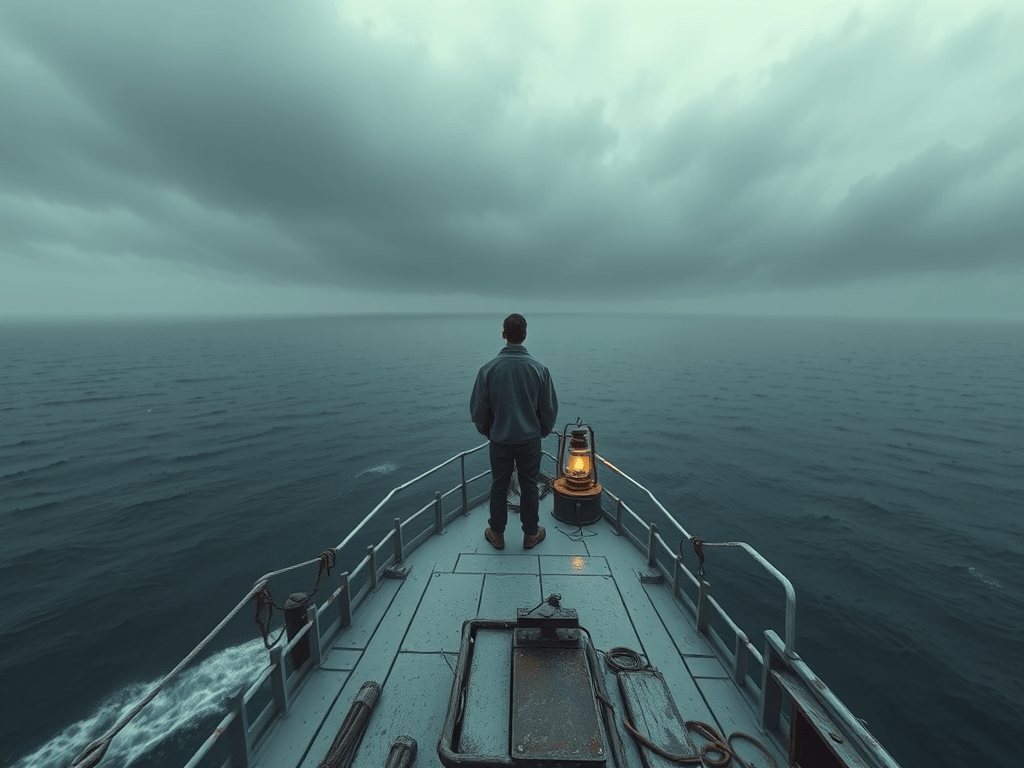

The story that follows happened during the winter of either 1995 or 1996—I can’t recall the exact year, but I’ve never forgotten the where, the what, or the why. Poverty produces a cold sting that goes marrow deep; one that lingers long after the privation fades. Fortunately, over time, that sting becomes a tool for cultivating gratitude. That gratitude is why I wrote this story down in 2011, and that same gratitude is why I post it now.

In the San Bernardino California National Forest, it is illegal to cut down trees in the wild. To do so without the proper permits is to warrant a fine, arrest, or both. In spite of that, I remember one Christmas when my mother and I decided to venture into the woods to cut down our own Christmas tree. We didn’t have the proper permits, but I hope that my story will help the reader to understand that sometimes, when life becomes as wild, dark, and cold as the San Bernardino National Forest, the weather permits.

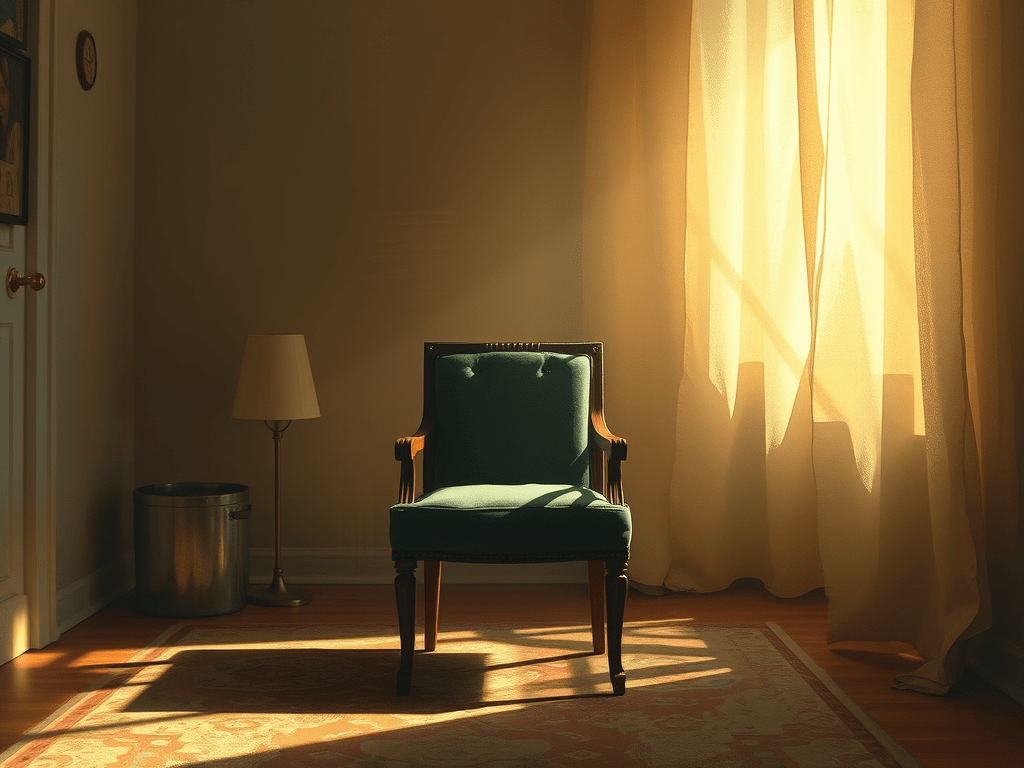

My mother hasn’t always lived a life that was respectable or easy to deal with. It was her addiction to marijuana, my stepdad’s addiction to heroin, and their combined addiction to any number of other substances, along with the scene that came with it, that eventually led to the falling apart of our family. My mom and stepdad split up, and my mom and I moved into the mountains. We had lost most of our belongings due to the fact that they were sold for drug money, or we simply left them behind. Therefore, the small two-room cabin that we moved into in Crestline, California was fairly empty, cold, and drab. My mother slept on the floor in the living room with her chihuahua, Lucas, and I slept in the small crawl space loft just above the living room. This configuration seemed acceptable most of the year since I was either off at school or playing in the woods with friends as a young 14-year-old should be doing. However, when the holidays came around, it became clear how poor we really were. Most of our meals came in the form of a canned ham that a local church would donate to us; therefore, ham for Thanksgiving wasn’t something that I was going to get excited about. What was even more discouraging was the thought of what Christmas was going to be like. There wasn’t going to be a Christmas tree. If my memory serves, my mother and I had made a pact that we weren’t going to purchase any gifts for each other. Not that we didn’t want to, we just didn’t have any money to do so. Thus, in effect, there wasn’t going to be Christmas at our cabin. As Christmas approached, the weight of wanting took its toll.

One day while walking through the woods on my way home from the school bus drop-off, it occurred to me that we didn’t need money to get a Christmas tree; we had Christmas trees all around us. There was only the matter of getting one from the woods into our cabin. I shared the idea with my mom, and we both decided that we could take the burlap sacks that we would use to gather firewood and cover the tree, once we cut it down, and carry it home.

We didn’t have a saw, a hatchet, an axe, or tools that would effectively cut down a tree of any kind. In spite of that, my mother and I marched into the woods determined to come back with a Christmas tree. We walked for about an hour, just far enough that no one would come and find us cutting down a tree, but close enough we knew we could carry our prize back to our cabin. We found a patch of forest where the trees weren’t too big, but big enough to make a respectable Christmas tree. Once we found one that seemed to suffice, then came the issue of solving the problem of cutting it down. Fortunately, some old off-roader had, many years ago, wrecked his truck in the woods and left it where it lay. The years and the mountain weather had rusted the truck so that the joints and the folds in the metal had become brittle and bendable. As a result, the jagged edge of the crumpled bumper would make a great knife if I could manage to get a piece of it separated from the truck. We gripped the flailed piece of metal and began to rock it back and forth in an effort to snap it free. After a few minutes of this, the bumper piece broke free.

After acquiring a sufficient tool for the job, I began the work of hacking, gnawing, and sawing at the base of our chosen tree. It goes without saying that the job was sloppy and painstaking. I needed to take frequent breaks, and once I got about two inches into the tree, I needed to move to another side of the trunk in order to cut the soft exterior; the hard interior wood was too tough to cut with an old truck bumper. My hands were getting raw and the cold metal made the job even more difficult as I didn’t have any gloves. About two hours later, the tree was loose enough that we could twist it and turn it, much like we did the old bumper, in order to separate it from the stump. Another 30 minutes later, the tree was free from it’s stump.

My mother began to wrap the tree in the burlap sacks and then stuff the sacks with tree bark and pine cones in order to make it look like we were merely collecting kindling for a fire. After our holiday package was all wrapped up, we began the job of carrying it back to the cabin. The first half of our journey was fairly simple since we had the woods to shield our progress. However, the last half of our journey was along the road side. And we knew that if we were caught, we would not only lose our Christmas tree, but we would be fined– and we didn’t have money to buy a tree, let alone pay a fine for one.

We decided that we would walk as fast as we could carrying a tree, and every time a car would come, we’d toss the tree to the side of the road and walk away from it. We must have tossed the tree to the side of the road three or four times before we made it back to the last small stretch of forest that took us back to our cabin. Tired and cold, we rushed as quick as we could. Most of the tree bark and burlap had fallen off, and it was now very obvious what we were carrying and what we were doing. Thus, the excitement, fear, and fatigue seemed to build more and more with every step. Finally and without incident, we made it back to our cabin. We flung open the door, shoved the tree in, and propped it up in an empty corner. We didn’t have a tree stand, so we used a metal soup-pot for the water and wrapped an old towel around the whole thing in order to hide both the pot and the haggard edges of the tree that the truck bumper had created.

We didn’t have any Christmas ornaments, tinsel, or lights, so in an effort to decorate our tree, we popped some popcorn that the church had given us and strung it up on some fishing line that I had. Also, we used aluminum foil to wrap around the tips of the branches to create a shiny effect. My mother also hung some small pieces of jewelry and other small odds and ends up on the tree in order to give it a fuller decoration. It wasn’t much, but it was our Christmas tree.

That is all I had written about the Christmas of ’95 or ’96, but as I recall it again now, I am sobered. My mother and I were both so sad, cold, and alone that year and for a number of years thereafter. We heated our small cabin only with wood from the surrounding forest, and if there was no fire lit, then mornings, showers, or return trips home were so cold we could see our breath indoors.

We were also so broke. I got my first job washing dishes at a pizza shop in downtown Crestline in 1996 for $5.25 an hour, and my mom was making about the same pay at a local motel on the other side of town. To subsidize our food, we walked the two or three mountainous miles to that church I previously mentioned. They regularly gave out ham, beans, rice, and canned fruit every few weeks. We didn’t have a car, so in order to get the food home, we had a grey, plastic trash can with wheels we’d use to pull the food back up to our cabin in the area of Crestline called Top Town.

I hated that trash can because I was the one that pulled it. When I pulled it, the school bus would often drive past. Mountain communities are isolated and small, so everyone knows if not your name, then at least your face. I didn’t want my face being seen pulling that trash can, but it was. I can still remember looking up as the bus rolled by only feet from my face. There are no sidewalks on mountain roads; there’s barely a shoulder, so any time a truck or bus passed, we had to physically scoot the trash can and ourselves out of the way. It was not only dangerous; it was humiliating. I hauled our groceries home, laundry to and from the laundromat, and excess pine needles to the trash– all in that damned grey trashcan.

That’s why my mother and I did all we could just to survive when we lived in on that mountain. We worked where and when we could. We accepted gifts and donations. We found happiness in the little things and in each other. We used what we could from the forest– like an illegally cut Christmas tree. Christmas trees aren’t necessary for physical survival, but they are for mental, emotional, and spiritual survival. When poverty tells a person “You’re too poor to participate in Christmas,” it’s necessary to tell poverty right back, “Fuck off, Grinch! I’m gonna get me at least a little Christmas!”

Life can be grinchy; it can often feel like whole eras are filled with nothing but pain and want. Crestline, California often felt like that for me. However, pain and want are some of the best teachers. In fact, they may be the most qualified. I’m glad I spent all the time I have with them both. They taught me that sometimes, when life becomes as wild, dark, and cold as our national forests, the land (not the government) will permit people all they need to survive.

One final note:

I looked up that old cabin, and it’s still there at 4594 S. Village Lane, Crestline, CA— looking as poor and drab as ever. On Google Street view, I can see the one small window above the front door that looks down on the street. That was my bedroom loft. I used to sit on my floor mattress, looking out that window, wishing I was somewhere other than that shit town in which we lived. The pine trees and Lake Gregory nearby helped soothe the sting of that place, but it was and still is an isolated little shit town in the mountains.

I don’t have any photos of my mom or me in that old cabin, but I do have two old photos of my mom’s beloved chihuahua, Lucas, and our old cat, Booger. Lucas can be seen sitting on the old couch we eventually got in the living room. It allowed my mom to no longer need to sleep on the floor. Booger and Lucas can also be seen in my bedroom loft, just in front of my floor mattress; the same one I use to lie on looking out that small window. These two pictures don’t tell the story of poverty I relayed above, but that couch and that mattress, along with a small table in the kitchen, were pretty much the only furniture we ever had in that place. Some may call it simple living; I called it poverty. At least Lucas and Booger never knew how hard those winters in the damn cabin really were.

Leave a comment